Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Truth or Consequences, NM

Sent via BlackBerry from T-Mobile

Monday, September 28, 2009

Post-WWII economic development in a tin can

This is not news, but I am struck by seeing the formula repeated mile by mile. So basically what's being offered is a slot in some harmful industry, sure to brutalize workers and violate others, or paltry wages in a less harmful industry where the profits don't even get reinvested locally. Certainly time to get off the highway.

Sunday, September 27, 2009

High plains driftin

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It's been way too long since I've posted - too little time between mad dashes and whirlwind visits. I'm in north Tejas on my way to Truchas, NM where I get to hole up and write for a couple of days before heading to Las Cruces and then Tucson.

I caught a high plains sunset last night. I hadn't realized or remembered how stunning these big sky vistas are. Their gentle rolls are lush green, probably in part because of the recent rains, and peppered with small trees and bushes - so different than the flat, golden expanses I grew up on.

But, OK, a strip mall lament [the old parts of Hwy 1 in Ft Lauderdale & Miami are, of course, fine exceptions]: the scale of strip malls is expanding to more mini-mall size along with dually/Hemi-scale trucks and jumbo houses. And on a road trip level alone, they kill the romance of high plains driftin. But so where do convenience and perspicacity and serendipity meet and where do they diverge?

From a pecan stand [not as quaint as it sounds] in Chillicothe, TX

Next posts: "From camo to corrections" and Preparing for family separation

Sent via BlackBerry from T-Mobile

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

University of California Walkouts & G20 Mobilizations

On the G20 meetings and protests in Pittsburgh this week, check out Defenestrator's special issue "What's next: Build it from below, alternatives to capitalism" and Rob Eshelman's posts @ The Nation.

With solidarity to you all from Austin.

Saturday, September 19, 2009

Back to Eastern Kentucky II - via New Orleans, Brooklyn, New Bedford, Guatemala & Italy

I’m trying to figure out a way of conceptualizing and researching what I’m imagining as abolition economies. So here’s how I’m thinking about it now. Prisons and exclusionary/punitive migration policy are technologies of dispossession that deepen existing racial and class relations. For example, felon disenfranchisement and nationalistic regulation on employment make it exceedingly difficult to work, as an employee or in licensed trades. So what do folks do to make a living, and how can these alternative economies be built on as a source of resistance to the systems of oppression and dispossession? Kernels for these ideas come from a conversation I had a couple years ago when I first visited New Orleans and interviewed Shana Griffin of the New Orleans Women’s Health Clinic (unfortunately now closed, it seems). She told me that part of ending violence against women meant rebuilding community economies and infrastructures. If we were to think about community gardens or neighborhood businesses, within this thought are responses to the structural violence of hunger, of industrial food production, the economic exchanges that can circulate in a neighborhood rather than through big box chains, the social ties that can be fostered through particular community institutions, etc. And this can be the case with prison-siting, too. Since the 80s, prisons and contracting for prisoners have been sold/used as a form of economic development, but places that are already poor when they build a prison stay just as poor; this is a nutshell of Gregory Hooks’ research. I’m paraphrasing, but Ruthie Gilmore once pointed out that unplanned distribution of a pot of money to folks living around a prison would be a more effective economic development model. The point is that much better can be done than that or prisons, so that’s where she looks at what she calls grassroots planning – what are the alternative futures that people want to create for themselves, their kids, and their communities?

Cultural economies can be an important aspect of this project. My conversation with Nick @ Appalshop about cultural work and youth media education and time in New Orleans help make these connections real. Fatalistic resignation to a future of harmful industries and livelihoods rests on a naturalization of these harms (fatalism and fatality). And it rests on forgetting past struggles and losses – remembering a struggle that was lost or crushed is entirely different than thinking that there has never been opposition and no possibility for change. The dispossession of memory is a dispossession of histories of creativity, identity, and struggles as a resource for change. Creative projects can recognize and revalue this past and present are part of the capacity of resisting more harms. Finding that one has a claim on a place and a future goes hand in hand with finding how one’s going to make that claim. Is it writing, film, music, community building, documentation, poetry, what all? If, it seems to me, alienation from cultural production is a huge part of how people can be rendered politically passive, creating the conditions for expression and change is part of people coming to learn their power. So the young person who decides to make music rather than follow the well-worn paths to prison or the military or other harmful industry can be read as an act of refusal. When consciously and collectively acted on, this can be a prefigurative project of bringing into the world the future one wants. This same idea I also experienced in Asheville and Athens around locally grown food. And in New Orleans, where I write this post, Jordan Flaherty tells me that cultural workers are central to rebuilding community institutions. This is as much about the amazing arts that are produced here as the social sensibilities and relations that are created.

I’m talking mostly about the practices and social relations of these intentional economies, but a perfect illustration is a bag I am taking with me across the country. Just before leaving on this trip, Silvia Federici, George Caffentzis, and I were talking about the effects of migration policy, the appalling situation for migrants in Europe, and immigrant activism and solidarity.* At some point the conversation came to networks of mutual aid and solidarity, and Silvia brought out this bag. It was made by women who had been arrested in the New Bedford, Mass. ICE raid @ a factory making materiel for the US military. Most of the women arrested are from Guatemala, a place in which the US has a sordid history of military and economic interventions. The bags are a project of forged out of necessity, which also capture multiple layers of displacement, violence, and dispossession. But they are also a kernel of anti-violence and facilitate circuits of a solidarity economy.

With that, off to a night of music to raise money to re-open Charity Hospital.

*Here’s an email I just received for a day of upcoming actions in Italy:

CALL Antiracism ROME

October 17

National events

PIAZZA

DELLA REPUBBLICA 14.30

,1989 Hundreds of thousands take to the streets in

Rome for the first major demonstration against racism.

On 24 August of that year at Villa Literno, in the province of Caserta, had been killed a South African refugee, Jerry Essan Masslo. Just 20 years later, racism has not been defeated, continues to cause fatalities, and is powered by the Berlusconi

government. The security package passed by the center-right government offends

human dignity, introducing the crime of "illegal immigration". The death of

immigrants in the Sicilian Channel, which is turning into a graveyard marine, is

the tragic result of the inhuman logic that guides government policy. This

dramatic situation is dangerously in society and legitimating fueling the fear

and violence against any diversity. It 'time to react and build together a great

response and solidarity to fight to defend human rights by rejecting any kind of

racism.

Therefore we appeal to all secular and religious associations, trade

unions, civil society and all movements to the streets October 17 to stop

the spread of racism based on this platform:

* No racism

* For the legalization generalized for all

* security

* Reception Retreat Package

* No for all the rejections and the bilateral agreements providing

for them

* For the clean break of the link between residence permits and

employment contracts

* Right of asylum for refugees and displaced

* To the final closure of the Centers for identification and expulsion

(CEI)

* No divisions between Italians and foreigners

* Right to employment, health, housing and education for all

* Maintenance of the residence permit for those who have lost their jobs

* against all forms of discrimination against LGBT* Solidarity with all workers fighting to defend work

Friday, September 18, 2009

Road trip day 5 - back to eastern Kentucky, part 1

After staying the night in West Virginia, I traveled to Whitesburg, Kentucky to meet with Nick Szuberla at Appalshop, just across the state line from Wallens Ridge in Virginia. Appalshop is a multimedia arts and education center started with War on Poverty money in the 1960s. The question then as now is how the arts can foster social and economic justice in a place whose economy has been dominated by coal.

The remoteness of Whitesburg belies its connection to globalization. The mechanization of the multinational coal industry created even greater unemployment in an already struggling region. With a prison located atop an old mountaintop coal removal site, we have one story of how a place reliant on extractive industries tries to retool its economy. With Appalshop, we have another story of how building cultural resources and capacities can be a source of resistance and a cultural economy that provides alternatives to the deadly paths to the mines, prison (as guard or guarded), and military.

I’m here to learn about the Thousand Kites project, which has become an important communication and cultural infrastructure linking imprisoned folks and their families and communities on the outside. Amelia Kirby and Nick started the project about 10 years ago soon after Red Onion and Wallens Ridge opened. Appalshop’s radio station broadcasts reach the prisons and they began hearing stories about prisoner abuses and decided to do a project on the prison system. Over the years they (and countless other folks) have created several projects, including a film, Up the Ridge, a weekly radio broadcast, Holler to the Hood, and the yearly Calls from Home radio program, which is syndicated to over 200 radio stations across the country. Ms. K in Richmond, VA, whom I interviewed when I first started the trip, is on the air every week and uses the broadcasts as a powerful mobilizing platform. Likewise, the radio and documenting personal narrative has also been used to bring prisoners back to the states where they were convicted. Wallens Ridge is among the prisons that contracts with places outside Virginia, such as New Mexico, DC and the Virgin Islands to rent space for prisoners.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Cruelty & Invisiblity

Under the Bush administration, a seeping, sometimes galloping, authoritarianism began to reach into every vestige of the culture, giving free rein to those anti-democratic forces in which religious, market, military and political fundamentalism thrived, casting an ominous shadow over the fate of United States democracy. During the Bush-Cheney regime, power became an instrument of retribution and punishment was connected to and fueled by a repressive state. A bullying rhetoric of war, a ruthless consolidation of economic forces, and an all-embracing free-market apparatus and media driven pedagogy of fear supported and sustained a distinct culture of cruelty and inequality in the United States. In pointing to a culture of cruelty, I am not employing a form of left moralism that collapses matters of power and politics into the discourse of character. On the contrary, I think the notion of a

culture of cruelty is useful in thinking through the convergence of everyday life and politics, of considering material relations of power - the disciplining of the body as an object of control - on the one hand, and the production of cultural meaning, especially the co-optation of popular culture to sanction official violence, on the other. The culture of cruelty is important for thinking through how life and death now converge in ways that fundamentally transform how we understand and imagine politics in the current historical moment - a moment when the most vital of safety nets, health care reform, is being undermined by right-wing ideologues. What is it about a culture of cruelty that provides the conditions for many Americans to believe that government is the enemy of health care reform and health care reform should be turned over to

corporate and market-driven interests, further depriving millions of an essential right?

What Giroux captures is feeling really visceral to me on this road trip when military bases and detention centers pop out of nowhere and just as quickly recede, and when a friend tells me about a white mob @ town hall meeting on health care. What kind of health system could possibly be created when some politicians are working "to make sure the health plan did not become a magnet drawing new illegal immigrants to the United States"? The nativist, racist animus that would see spending $8 million to keep 8 undocumented people off the health care rolls speaks not only to a sort of blind fury, but also to the many times in the past when white folks have cut off their own noses to make sure other folks don't have basic services.

Monday, September 14, 2009

Columbus to Lumpkin, GA

Happenings around Highlander Center

Sunday, September 13, 2009

North Georgia Detention Center - Gainesville, GA

Saturday, September 12, 2009

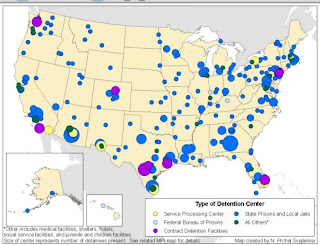

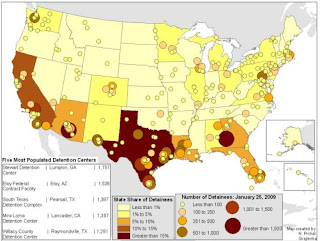

Snapshot of Immigrant Detention January 09

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Vic Chestnutt Dogging My Heels

So I noticed while I was in Philly (I think) he'd be playing after I left, and then again in Asheville two days after I would be leaving town. What is up with that? Was trying to figure out how to drag out my time, but turns out he is based in Athens, so maybe catch a show here?! But Athens folks are treating me so good, not sure if we'll be able to stop chattin long enough!

Umm, real quick other shout out to all my fab friends for the road music. You all have the most awesome and most awesomely eclectic taste in music - so rocking! Headed down to Decatur for an interview, and then will try to catch back up with all the fine folks I've been talking with over the past few days.

Virginia Prison Town Part II

Silly me, but I forget it’s Labor Day weekend until I begin to make my way out of DC on the Friday afternoon before the holiday, and get myself a fair dose of the notorious Beltway traffic. I’m headed through the Shenandoah Valley - the Alleghenies are on my right and the Blue Ridge Mountains on my left as I make my way south and west to southern Appalachia [k, folks in the know – the geography’s all new to me, so tell me if I’m getting these places mixed up!]. I’ll be staying then nite near The Greenbrier in West Virginia, a huge resort that was the site of a once secret Cold War installation to house the president and executive branch.

I make my way to Harrisonburg, VA to meet with Patrick Lincoln, who does organizing work with The People United, a multi-issue, multiracial organizing network. Harrisonburg’s economy is fairly robust and diversified with agriculture, manufacturing, universities, and R&D; and Rockingham County, where Harrisonburg is located, is one of the few 287(g) jurisdictions in the country. This agreement seems to have been made quietly, and some 40 immigrants are held in the jail on any given day. And 287(g) is the prime explanation the sheriff gives to justify his desires for jail expansion. Day to day work goes on with people who are held there.

Patrick puts another layer on this convict leasing (prison space renting) that Ms K talked about. In the fall of 2008, the group learned about a plan to build the “mid-Atlantic hub” for ICE detention in Farmville, VA after planning was well under way. They and other groups quickly mobilized a campaign, holding meetings with business owners, environmentalists, students and local media.

One city counselor defended the project saying:

“We’ve been hearing horror stories about detainees being put into prison with other criminals when all they have done is be here without documentation. Our goal is to keep them safe,” Spates continued, “But I want to be honest with you.Likewise, an investor in the facility cited the need to keep immigrants detained away from criminals:

We do stand to gain financially from this.”

“You’re taking folks who aren’t criminals and you’re making a jail system house them. You’re treating people who aren’t criminals as criminals.” (Source: Virginia Organizing Project)

In the midst of the campaign, high profile press coverage (Washington Post, New York Times) was directed at the area following the death of an immigrant in the nearby Piedmont Regional Jail, and ICE’s subsequent removal of detainees from that facility. With this negative press, it seemed possible to derail the project and one month later in March, 2009, they held a march where folks from Mexicanos sin Fronteras, The Defenders, and indigenous leaders from the Tidewaters area all gathered. The local newspaper editorialized against the plan, but the project was too far along by the time people learned of it to halt construction, which is now underway.

Now there are plans for another immigrant detention just over the ridge from Harrisonburg in Pendleton County, West Virginia. Patrick emphasizes the differing political economy of these sites. In Farmville, the city council initiated the proposal; Immigrant Centers of America, a company already doing ICE contracting in Virginia, would run the facility. In West Virginia by contrast, the county was approached by a businessman in the transport and warehousing industry, whose family has ties in the region. [This is a rich irony considering that warehousing and transport is a fairly accurate description of what prisons do.] There is some local opposition to the project already brewing, some of it anti-corporate and other anti-immigrant. And so there is a question on how/if that conversation can be moved while preventing the detention center. This is an ongoing campaign, so I plan to keep following it and posting any new news/calls for support, etc.

So now Virginia is a different kind of border state. The geopolitics of the US-Mexico border and NAFTA-led restructuring of manufacturing, agriculture, and migration is building on and butting up against the post-bellum North-South border of race, class, and federal relations. To the racial stereotypes of Black people as drug users or gang members and Latinos as drug runners or gangbangers, there is the additional discourse of nationalism justifying massive policing and violent exclusion. In a national moment in which race is supposed to be over or where we’re supposed to be multicultural, the law is the place where race is delineated and simultaneously obscured. Blunt racial stereotypes grease the skids of hyper-policing and prison expansion, and overt racism is legitimated by virtue of the law (“they’re criminals,” “they don’t deserve anything because they broke the law”). Discourses about “the worst of the worse” facilitate expansive police powers, including traffic sweeps, sentence inflation and harsher conditions of detention, and legitimate abuses of power.

Both Lillie and Patrick discuss the ways in which politicians and government officials rely on the “worst of the worst” to legitimize prison expansion and treatment of prisoners. If it weren’t for their work, the line goes, then there would be more crime and more terrorism. This cycle of fear-mongering and institutional legitimation [wasn’t it Tilly who wrote about the state as a racket?] has an expansive logic that continually justifies new demands for power. Police, like military, claims that they are responsible for safety and security makes questioning abuses of power so difficult because, as Lillie observes, such questioning is tantamount to disloyalty to the community. This is why reframing the terms of community and safety is so imperative in terms of questioning the justness of the law rather than the frames of the criminal. Battling out who’s the good versus bad criminal or good migrant versus bad doesn’t do much to intervene in a cycle that determines community and safety by virtue of exclusion.

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Prison Town Virginia I

Monday, September 7, 2009

Appalachian Prison Belt

"Surely the State Is the Sewer"

I make my first stop here to visit Eastern State Penitentiary. I’m fascinated by the place that Quakers advocated as an improvement over the city jail and rehabilitative reform (they’ve since issued an apology). While not the first penitentiary in the nation, Eastern State (followed by Sing Sing in New York) became a model for prison construction around the world. By the time it was built, it was the most expensive government building constructed to date and had the most modern of infrastructure: plumbing for fresh water and sewer and central heat.

Both of these details sit with me – what does it say about this nation’s ethical and spiritual (in the broadest sense) commitments that the most expensive building would be a penitentiary – the latest of technological and social marvels? What does it mean that this represented a forward-looking, if not righteous, reform?

When talking about this later with Dave, I recall a series of recent articles on Homeland Security’s announcement that it would be reforming the existing system of detention where immigrants are confined in some 350 ICE detention facilities (public & private), and city and county jails. ICE is forming a new Office of Detention Policy and Planning that will be charged with creating what ICE director John Morton called a “truly civil detention system.” The New York Times touted the move to regularize the patchwork system as “humane.” It feels like a moment akin to the establishment of ESP; how does “truly civil detention” so easily slip to “humane”?

In equating “humane” with “civil,” the Times concedes detention as humane, and fails to question detention as the civilized “solution” to migration. Stories printed elsewhere report that the “new detention centers will be more like secure dorms than jails.” The imagery of detention as a supervised summer camp or college living experience is part of the humanistic appeal of this reform. As when prison reformers who brought about Eastern State railed against the co-mingling of people who had committed different crimes in local jails, the Times claims that the problem is that the current system is too much “like a system to warehouse and punish dangerous criminals, which immigration violators overwhelmingly are not.”

The Times paints everyone in the criminal justice system as already criminal and dangerous, but this move to separate the good from the bad offender will ease the formalization of civil (in the legal sense) detention, making it a permanent feature in the political landscape. The equation of “secure” with “safety” obscures coerced confinement as an issue of freedom and of punishment, and the abuses that inevitably take place in such conditions. But this distinction between civil and criminal offenses won’t mean safety, just expansion of facilities and categories of acts that are jail-able. Indeed, even with alternatives to detention like ankle bracelets, ICE director Morton has said: "I don't think the overall number of detention beds will decrease significantly. It will remain roughly the same."

The significance of the formalization of detention was shrouded by the announcement that DHS would close the Hutto family detention center in Texas, which has been the site of concerted activist pressure. This will leave the nearby Berks family detention center as the only one in the nation, which county officials are apparently reconsidering because they’re not making enough money from the contracts.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. On our drive across the city to Eastern State, Dave tells me about what’s been going on in the city. Over the summer there have been several shootings in his neighborhood, and within blocks the row houses turn to (small) mansions as we approach the Penn neighborhood. We pass by MOVE’s new house and then the more stately rowhouses near Eastern State, which are once again in the favor of the gentry. Philadelphia faces a $1 billion budget shortfall, and the mayor’s latest budget promises to cut staffing at parks to 15 total, reduce the numbers of trash pick-ups, and there have been talks of closing the city pools. The cooler weather’s not exactly the reprieve residents would want for such an essential facility, but the successful pushback on closing city libraries is significant, and folks have also been organizing around the pools.

And so, “Surely the state is the sewer,” as Dominique Laporte wrote. And so now the prison is still being built with the latest technologies even as Philly and other cities crumble. Prison construction brought us the sewer, but now the sewers and other essential infrastructures are sacrificed to the prison. Yet, as when ESP was new, people lament how prisoners have services that the rest of folks do not. This lament is a desire to make conditions inside worse rather than treating the expansion of prison as part and parcel of the crumbling of living conditions on the outside. The extent to which the prison will be seen in contradiction to the prisons or schools or health care or roads will be a matter of political education and recognition that the reforms instituted for the inside will hardly be kept within prison walls. Projects like the ArtJail, the brainchild of Albo at Philly’s Wooden Shoe Books, links the deconstruction of public education with the construction of prison: the school to prison pipeline, and does just this work in a smart, creative way.

*Thx to Shiloh for Laporte quote. K “Surely the state is the sewer.” Dominique Laporte “The history of shit” MIT Press.